This is one of those personal projects that I worked on late at night. The code might not be my best work, but the application runs well, it’s fun to play against, and I learned a new algorithm from it.

TL;DR

I built an AI that can play a perfect strategy of Tic-Tac-Toe without machine learning and without storing every board state in a table. The algorithm is a classic one in many AI textbooks called Alpha-Beta Pruning. I’ve put the code in this GitHub repo for anyone to play against.

Preamble

One way to model practical reasoning in AI is as a search space of possible outcomes from available actions. There are many dimensions on which to define the search space in which an AI algorithm operates, e.g. fully observable vs partially observable, and the first definition of the search space along these dimensions is the first fundamental task of applying AI to real world problems.

AI Researcher will often use games to develop new AI algorithms because games have well defined rules for which they can easily be categorized along these dimensions. There’s the original DQN algorithm that famously learned to play Breakout at a super-human level using reinforcement learning. But reinforcement learning has two traditional drawbacks: it has long training times and its unable to reason about long term plans. The former is obvious for reinforcement learning algorithms. We know the latter because the same paper that brags about their superhuman performance on reflex and speed-oriented games showed terrible performance on the games that required reasoning about moves just a few moments in the future (e.g. Ms. Pac Man and Montezuma’s Revenge).

But before reinforcement learning, there was symbolic AI that used objects and concepts from traditional computer science to reason about possible series of actions. Relevant to this project, in 1961 Hart and Edwards first developed the alpha-beta pruning which models the set of possible actions as a tree (a familiar concept in computer science) and prunes unrealistic branches of the tree to improve performance.

Discussion

The simplest (and dumbest) way to solve Tic-Tac-Toe would be to store all the possible board states in a hash table and call the best possible move from that hash table. With only 3^9 (or 19,683) possible board states and with each board state only consisting of an string or integer array of length 9, this could easily fit into memory. But this would be no fun to play against and would be painstaking to build.

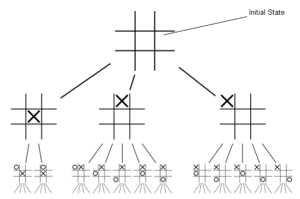

Instead, the alpha-beta pruning algorithm models the search space as a tree of possible moves in each state. For the first move of the game, this means there are (very roughly) 9! (or 362,880) possible path-dependent end states of the Tic-Tac-Toe board for the algorithm to consider. But this complete search of all possible moves isn’t intelligent, and it certainly wouldn’t be feasible for real-world applications of AI where the “board” is larger than 9 squares, so to speak.

The alpha-beta pruning algorithm improves on complete search by pruning the branches that make unintelligent moves (i.e. moves that lose the game for the player when there is are better moves available) It does this by assuming that the opponent will always make the optimal move in every situation (i.e. that the opponent is rational). The simplicity of the algorithm is that it simulates the intelligent versions of the game by treating the two opponents as using the same strategy, that is, maximize my likelihood of winning given a board state. This is easily applied to Tic-Tac-Toe because there isn’t too much strategy involve besides just winning the game. This computerphile video explains the application nicely. This is an excellent example of a recursive algorithm in which the core function simply inherits a board state and chooses the optimal move based on a recursive call to itself for each of the available moves. In each call, the board is “flipped” and the AI simulates the move for the other player, so see what board states come out at the end game. After the AI simulates the all the intelligent versions of the game, it makes it’s first move.

I’ve implemented alpha-beta pruning for Tic-Tac-Toe and put the code in this GitHub repo. I’ve also done the same algorithm, along with the original mini-max algorithm from which alpha-beta pruning is derived, for mancala in another GitHub repo. The core algorithm is the same between the two projects. The only major difference is that the mancala-playing AI has a maximum search depth where-by it estimates its probability of winning using a utility function rather than calculating the precise probability by simulating to the game to the end. Even with this search depth limit, the AI is still nearly impossible to beat by a human player (and with no training required by the algorithm!).

Final Thoughts: AI vs ML (reinforcement learning)

I’m still shocked when I hear people conflate machine learning and artificial intelligence. ML is a discipline of statistics that intersects with AI, but implementations of algorithms such as alpha-beta pruning plainly demonstrate that intelligent decision-making doesn’t require necessitate statistical methods or long training times or “writing if-then rules”. This implementation alpha-beta pruning algorithm performs its decision making during real-time game play.

However, neither approaches to AI are in any way similar to what a human might do to reason through a strategy for Tic-Tac-Toe (e.g. simplifying their options by noticing the symmetry of the board (did you notice the header image of the search space reveals this symmetry?) or realizing there’s more connections to be made from controlling the center of the board rather than the corners). Despite these shortcomings, both of these mancala and the Tic-Tac-Toe AIs are fun to play against. It’s surreal losing a game to an algorithm that you wrote.

Credit goes to the free online AI textbook: Artificial Intelligence: Foundations of Computational Agents, by David L. Poole and Alan K. Mackworth