In a previous article, I introduced my Machine Vision course project in which I trained a U-net deep neural network architecture for building extraction from satellite images over Khartoum, Sudan. The U-net model performed image segmentation quite well, after which I developed a post-processing pipeline to evaluate the model on building detection, in which it unequivocally performed poorly. The purpose of this article is to go over why I think the model performed so poorly and how I could improve upon this performance in future iterations of the project.

Critical Evaluation: Segmentation

In the first stage of this workflow, the U-net model was trained to segment the satellite images which gives each pixel in the image a value between zero and one: 1 for building, 0 for not-building. In the first iteration of this project, I experimented with custom-built U-net architecture using PyTorch that did not include the pretrained ResNet34 encoder as I’ve described in the previous article. I assumed that a ResNet34 encoder wouldn’t have a significant impact on our model’s performance because it’s trained on the ImageNet dataset which is not primarily satellite imagery, but this reduced U-net only achieved a per pixel F1-score of 0.723 compared to 0.801 for the full model with the ResNet34 encoder. Still, it’s not clear to me whether this increase in accuracy came from the superior architecture design of the ResNet34 encoder over the standard U-net architecture of convolutions, ReLu activations, and downsampling or from the pretrained weights themselves, but this does highlight the importance of model selection. For future iterations of the project, I’d like to experiment with more U-net variants. Two notable architectures are FeedbackNet and SetNet which have both been deployed successfully for building extraction tasks in developing countries [3] [2] [1].

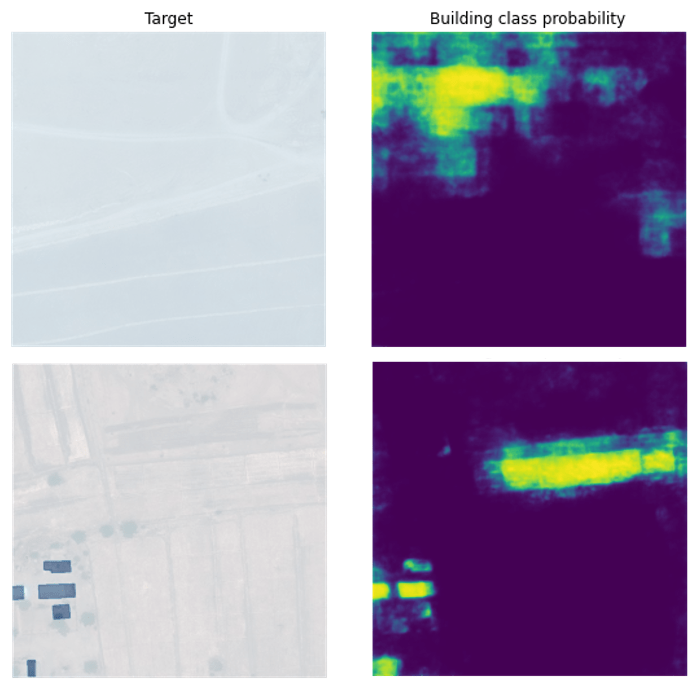

While the F1-score for segmentation was reasonably high, the model’s performance measured by Intersection over Union for segmentation was slightly lower: 0.64, which suggests that the model suffered from false positives more than false negatives. By visualizing some of the prediction maps from this model, we can see that this model tends to hallucinate buildings around farmland and highways, as shown in the image below. This is understandable considering that the hard edges of roads and farmland have the distinct signature of being man-made while also having a similar color to many of the concrete and brick buildings made from local dirt and clay. I believe this problem can be solved by creating distance maps as segmentation targets, which will be described in more detail later in this article.

There were a few occasions of false negative predictions (i.e. the model ignored a building in the image) when evaluating the model. The image below shows the largest error of a false negative in the dataset. There are three buildings with the same shade of dark roof that the U-net completely missed in its prediction. This could have been caused in part by the lack of dark roofs in the training dataset or by the fact that the roof color looks similar to the dark green of the trees and bushes in the region (seen in the lower right hand corner of the image below). To address both potential issues at their source, I’d like to gather a larger training dataset and also use all 8-bands (particularly the IR band) of the dataset for training the model. The former is unlikely to happen anytime soon on my budget, but the latter would required some small architectural changes to the input layers of the U-net to accommodate 8-bands instead of just 3. Infrared (IR) light is absorbed by the water content in the trees and bushes and is therefore distinguishable from other green objects in 8-band images. The black-and-white images below illustrate this point for this particular false negative, but in short, I think a U-net trained on 8-band images would have fewer false negatives than my current model.

Critical Evaluation: Detection

After image segmentation, I applied a custom post-processing pipeline for building detection from the U-net’s image segmentations. While segmentation attempts to label each pixel as either building or not, detection attempts to identify objects as coherent groups of pixels within an image. For example, building detection algorithms will ideally seek to identify two buildings that are near each other as separate buildings while segmentation is only concerned with labeling individual pixels values as building or not-building.

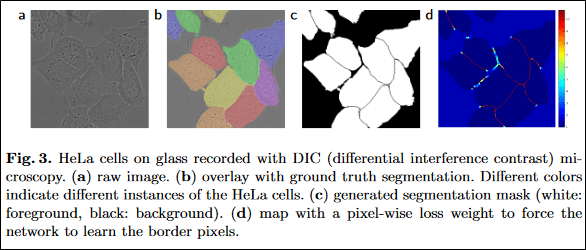

Despite my best efforts, my post-processing workflow only achieved a per building F1-score of 0.201 which was largely caused by the model’s inability to separate closely spaced buildings. I’ve identified two potential solutions to this problem, both of which involve modifying the target segmentation map for training the U-net. The first solution can be found in Equation 2 in the original U-net paper (presented below) which details how to generate distance maps that will yield high penalties for regions between closely spaced objects [4]. This is one of the key factors contributing to how the original U-net model achieved such successful image segmentation on images of cells, which often have even less clearly defined boundary edges than the buildings in my training dataset. It is likely that using this method to penalize the model for merging small buildings could improve the building detection F1-score significantly.

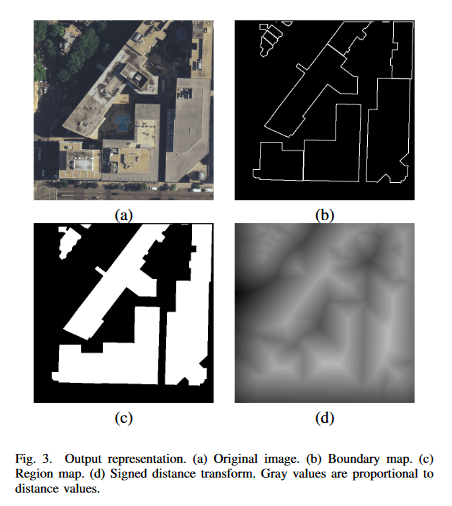

The second technique that I’ve identified for improving the U-net’s building detection accuracy is also a pre-processing method for the training data using distance maps. Yuan (2016) created the distance maps shown below by setting the pixel value in the target map equivalent to the pixel distance to the nearest border, with pixels on the interior of buildings having positive values and exterior pixels having negative values. This puts a higher penalty on false positives (addressing the hallucinating-buildings problem that I mentioned before) while also giving buildings some spatial structure for the model to learn.

Learning the internal structure of buildings is a crucial feature for the post-processing pipeline that I developed because it uses a greedy algorithm on the prediction maps to separate individual footprints in the predictions. This greedy algorithm tended to break apart large footprints into smaller chunks, resulting in multiple “missed” buildings even when the U-net correctly identified the entire footprint of the building. Providing the U-net with the internal structure of large buildings would help the model generate prediction maps that are smoother and more amiable to this greedy algorithm. This is particularly helpful for the buildings in our training dataset which have highly textured roofs (which are numerous in this training dataset). I expect this to be one of the largest sources of discrepancy between the U-net’s performance between footprint and building detection.

The two improvements that I’ve mentioned about involve changing the pre-processing pipeline before training. There also exist some techniques for improving the post-processing of the segmentation result from the U-net model. Some researchers have improved model performance in some cases by creating bounding boxes around segmentations instead of the greedy algorithm that I deployed, and others have found success using dynamic thresholds techniques to improve building count estimation. Both of these methods will be considered for future expansions of this project.

Conclusion

For me, this project revealed the difficulty of working with GIS data and Satellite Imagery, especially when you are new and unfamiliar with them. It’s a different set of programming tools that I’m used to, and I went through a very steep learning curve with this project, which is partly revealed by how incomplete the project is relative to my ambitions for it. At the end of the project, I still had several ideas of how to improve it but simply ran out of time in the semester. That being said, this was by far my favorite deep learning project that I’ve worked on so far. It was extremely demanding, and I really got to put everything I knew at the time into this project. I’m really looking forward to going much deeper into GIS data and Deep Learning in the future. The applications for this type of technology, both humanitarian and commercial, are nearly endless. Both subjects are huge topics to explore, and I’ve already started looking for resources to help me get a solid foundation on them. Feel free to reach out with any suggested learning material.

References

- Tobias G. Tiecke, Xianming Liu, Amy Zhang, Andreas Gros, Nan Li, Gregory Yetman, Talip Kilic, Siobhan Murray, Brian Blankespoor, Espen B. Prydz, and Hai-Anh H. Dang. 2017. Mapping the world population one building at a time. arXiv:1712.05839 [cs.CV]

- Vijay Badrinarayanan, Alex Kendall, and Roberto Cipolla. 2016. SegNet: A Deep Convolutional Encoder-Decoder Architecture for Image Segmentation.arXiv:1511.00561 [cs.CV]

- Xianming Liu, Amy Zhang, Tobias Tiecke, Andreas Gros, and Thomas S. Huang. 2016. Feedback Neural Network for Weakly Supervised Geo-SemanticSegmentation. arXiv:1612.02766 [cs.CV]

- Olaf Ronneberger, Philipp Fischer, and Thomas Brox. 2015.U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation.arXiv:1505.04597 [cs.CV]

- Jiangye Yuan. 2016. Automatic Building Extraction in Aerial Scenes Using Convolutional Networks. arXiv:1602.06564 [cs.CV]